35TH INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS

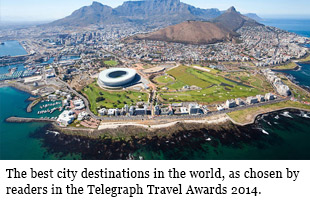

27 AUGUST - 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 | CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA

Sponsors

35 IGC SAGPGF

35TH INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS

27 AUGUST - 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 | CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA

My IGC

ExSA Post 2 : Northern Tanzania Trip, September 2016

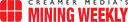

The group of a dozen geologists and spouses from countries as far afield as Australia, France, Norway, and the USA commenced the ten-day field excursion to northern Tanzania on 4th September. Despite a poor start with five delegates stuck at Nairobi airport for the first day, and problems with lost bags, the remainder of the excursion proceeded smoothly with good field conditions. The excursion was focussed on examining the geology of national parks, reserves, and conservation areas in a part of East Africa famous for some of the greatest concentrations of wildlife (Figure 1).

The IGC committee and the leader (RNS) express our gratitude to the guides and drivers Ray and Onesmo who negotiated the appalling Tanzanian roads with great skill and endurance and also to John Addison and his staff of Wild Frontiers who organized the excursion and looked after us with a high degree of professionalism. Local guides, including Samwely Lesekar who led his on hikes in the vicinity of Lake Natron and Jackson Tito, the senior scientific advisor at Oldupai Gorge who gave us an excellent overview of the geology and paleoanthropology of the area are also gratefully acknowledged. Of the many highlights of the excursion, the barren wastes of the Rift Valley in the vicinity of Lake Natron surrounded by giant volcanoes was possibly the most rewarding (Figure 2).

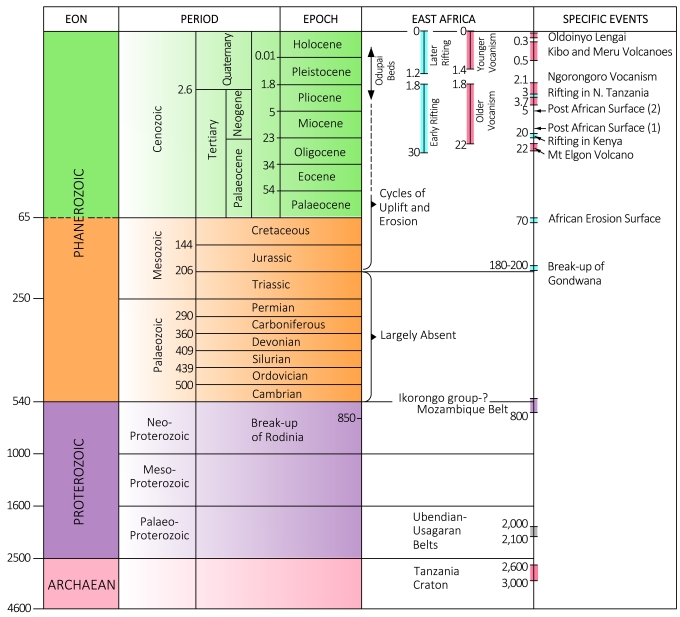

The geological framework of East Africa is dominated by two groups of rocks, the crystalline Basement and the East African Rift System (EARS) (Figure 3). The Basement includes sections of the Central African Craton, a stable block of mostly Archaean-age rocks, and the Mozambique Belt, the latter being an extensive Neoproterozoic north-south trending belt.

The Basement Complexes were subjected to various phase of uplift and erosion between the Jurassic and the Palaeocene (break-up of Gondwana). Rifting and volcanism associated with the EARS started during the Oligocene Epoch at around 30 Ma and resulted in regional domes considerably higher than the older, Gondwana- related land surfaces. Volcanism in northern Tanzania is mostly of Pliocene-Pleistocene age, as described by J B Dawson in a detailed overview published in 2008. Rifting and volcanism associated with the EARS has persisted into the Holocene.

Figure 3: Simplified Stratigraphic Column for the Gregory Rift Valley and surrounding areas of East Africa

Figure 3: Simplified Stratigraphic Column for the Gregory Rift Valley and surrounding areas of East Africa DAYS 1 and 2: Despite its small size, the Arusha National Park is one of the most spectacular in East Africa. The park is dominated by Mount Meru (4,560 m), a huge stratovolcano that rises more than 3,000 m above the plateau to the north of the regional town of Arusha. The volcano includes a giant caldera that developed around 8,000 BP during a catastrophic sector collapse that also produced the Momella event, one of the world’s largest debris avalanche deposits (volume of approximately 18 km3). The caldera includes a giant cone of ash and cinder that lasted erupted in 1910. The excursion included hikes in the caldera, an opportunity to enjoy the montane forest that envelopes the lower and middle slopes, as well as drives around the Momella Lakes where we were fortunate to see large flocks of greater and lesser flamingo.

DAYS 3 and 4: The Ngorongoro Conservation Area is an enormous area that covers a large range of ecosystems. The principle feature is the Ngorongoro Highlands, a large, extinct volcanic complex with an area of 90 km north-south and 80 km west-east. The highlands contains one of the natural wonders of the world, the Ngorongoro Caldera (22 by 18 km), part of the giant Ngorongoro volcano (2.5-2.01 Ma) with a diameter of 35 km. The drive through the caldera with lunch at the scenic Ngoitokitok hot springs was rewarded with an opportunity to view large herds of game and a variety of birds. The group observed that the south-western component of the caldera floor, which is covered by ash from Oldoinyo Lengai, supported the largest herds in the dry season. The afternoon included a hike into the Empakaai Caldera, the most northerly of the volcanoes in the highlands. The thickly forested caldera walls consist of trachybasalts in the lower part and nephelinite and phonolite in the upper part and the caldera includes a brackish lake with Pleistocene-and Holocene-age sediments.

DAY 5: This included a morning visit into the Lake Manyara National Park which is dominated by a finger-shaped, shallow lake typical of the region. Evaporation typically exceeds inflow and most lakes are saline and alkaline. The park nestles below a steep, thickly forested escarpment of the Rift Valley in one of the most scenic areas of northern Tanzania. The afternoon involved a long drive to Lake Natron which occurs in a hot (temperatures are regularly over 40 degrees C), desolate section of the Gregory Rift where vegetation is sparse and rainfall erratic.

DAY 6: The trek to the summit of Oldoinyo Lengai is generally completed in one day as there are no huts or established camp sites. Even with a pre-dawn start the ascent is strenuous (three participants attempted this and attained the summit after around 6 hours) and a guide is needed as the flanks of the cone reveal a radial erosion feature with steeply-incised, U-shaped gullies. The highlight used to be entering the active, northern summit crater, but this no longer possible. Additional treks include a walk onto the salt flats that surround Lake Natron, the waterfalls of the Engare Sero Gorge and fossilized footprints. The salt flats contain small freshwater streams and ponds that provide a variety of environments for aquatic birds. The extremely alkalinity is ascribed to high rates of evaporation and erosion of the juxtaposed volcanic cones that enclose the lake. The anomalous natrocarbonatite magmas (Oldoinyo Lengai and Kerimasi) react rapidly with meteoric waters and release huge quantities of sodium carbonate. The Pleistocene-age Gelai is a massive alkaline basaltic volcanic cone located on the south-eastern shores of Lake Natron. The fossilized footprints - they are preserved in an ash layer close to the surface - are of Homo sapiens preserved in volcanic ash derived from Oldoinyo Lengai (Figure 4). They have been dated at 120,000 years but this needs re-assessing on the basis of local knowledge of Masaai guides (noting presence of cattle prints and historical movement of the Masaai people) as well as the relative age of Oldoinyo Lengai. The gorge includes excellent exposures of the volcanism related to the Ngorongoro Volcanic Complex. Three principle features can be observed: thick beds of nephelinite lavas and ashes together with irregular debris flow deposits. The opportunity to swim under the waterfall and wade through the freshwater stream flowing from the Ngorongoro Highlands was enjoyed by some, as was the scramble along the cliffs (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Footprints of Homo sapiens preserved in volcanic ash derived from Oldoinyo Lengai, near Lake Natron.

Figure 4: Footprints of Homo sapiens preserved in volcanic ash derived from Oldoinyo Lengai, near Lake Natron.  Figure 5a: Hike into the Engare Sero Gorge included scrambling on the volcanic cliffs and wading through the stream.

Figure 5a: Hike into the Engare Sero Gorge included scrambling on the volcanic cliffs and wading through the stream.  Figure 5b: Hike into the Engare Sero Gorge included scrambling on the volcanic cliffs and wading through the stream.

Figure 5b: Hike into the Engare Sero Gorge included scrambling on the volcanic cliffs and wading through the stream. DAY 7: Another long drive, this time up the western escarpment of the Rift valley and through the Loliondo wilderness area onto the Serengeti plains. Large areas within the Serengeti Plains are contained within a world-famous national park that covers an area of some 14,763 square km. The dominant feature of the park is the seemingly endless plains that extend some 100-150 km westward and northward from the Ngorongoro Highlands toward Lake Victoria and the Kenyan border. The night was spent at the Lobo Lodge which is set around and upon a small koppie of Archaean-age granite with giant boulders.

DAY 8: This provided an opportunity for a full-day game drive and the unique chance to see large herds of wildebeest and zebra crossing the Mara River, in the northern extremity of the park, on their southward leg of the migration.

DAY 9: The drive south from Lobo Lodge towards the Seronera region provided an opportunity to examine the different geological terranes within the area. The dominant feature is the Archaean-age Central African or Tanzanian Craton. North-west trending belts of greenstones (2,810-2,630 Ma) include metamorphosed volcanic and metasedimentary rocks that are severely deformed and exhibit a schistose appearance. They crop out in low, bush-covered ridges or (more typically) are observed in river crossings, such as the Mbalageti River. The greenstones are enclosed by coalesced plutons of granite-gneiss (2,720-2,560 Ma) that crop out in clusters of koppies, such as the Moru and Simba koppies. We made a short hike on several koppies including the Gong Rocks where the Masaai have created hollows for ritual purposes. The Ikorongo Group is a localized sedimentary basin (NeoProterozoic-Cambrian) which we observed in fault-bounded hill slopes and around the Sopa Lodge. Large parts of the eastern Serengeti Plains are covered by thin layers of Holocene-age ash derived from Oldoinyo Lengai.

DAY 10: Exiting the Serengeti via the Naabi gate provided the opportunity to examine a koppie comprised of granite-gneiss associated with the Neoproterozoic Mozambique Belt. Quartzite and mica schist of the same system crop out next to the lo-level bridge over the Oldupai River en route to Oldupai Gorge. Oldupai is synonymous with the husband and wife anthropological team of Louis and Mary Leakey with finds including the major discovery of Paranthropus boisei (the original name Zinjanthropus - “Nutcracker Man”) in 1958. We were fortunate to be guided into the gorge and visit both the Zinjanthropus and Australopithecus habilis (or Homo habilis “handy man”) discovery sites (Figure 7) and obtain an overview of the stratigraphy including the Naabi Ignimbrite (1.9 Ma) in the river bed. Examination of a new trench in Bed I revealed the relative hardness of the tuff layers (ash from Ngorongoro) as well as the abundance of animal fossils. The ash from Lengai has also created the “Shifting Sands”, a popular tourist destination located near the gorge where isolated Barchan dunes of coarse-grained black volcanic ash occur. The afternoon included a long drive to the Laetoli site where a 27 m-long trail of footprints made by Australopithecus afarensis (3.6 Ma) and discovered by Paul Adell in 1978 were described and interpreted by Mary Leakey in 1981. The footprints - which are preserved in tephra of the Laetoli Beds – are covered by an extensive structure which is only removed for important visitors. We didn’t classify. A hike into the badlands of the adjacent river bed, however, was of interest as the deeply-eroded volcanic ashes contain numerous animal fossils. An overnight at the sumptuous Lake Manyara Lodge perched on the top of the escarpment overlooking the Rift was a fitting end to a long day.

by R. N. SCOON, November 2016

rnscoon@iafrica.com

Field trips

Field trips  Sponsorship & expo

Sponsorship & expo  Registration

Registration Tours

Tours  Promotion

Promotion

Conference Programme

Conference Programme  Field trips

Field trips  Sponsorship & expo

Sponsorship & expo  Volunteer

Volunteer  GeoHost

GeoHost  Registration

Registration Tours

Tours  Promotion

Promotion  Publications

Publications