35TH INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS

27 AUGUST - 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 | CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA

Sponsors

35 IGC SAGPGF

35TH INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS

27 AUGUST - 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 | CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA

My IGC

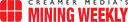

Cullinan diamonds

This is the English version of a story which appeared in the Afrikaans Sunday paper, Rapport, on March 8 2015. You can read that version here

Africa’s brightest Star still uneclipsed - Article by: Boris Gorelik

In January 1905, the world’s biggest diamond was found in South Africa. Who spotted it first? Who owns it now? And why hasn’t the record been surpassed in the 110 years? Boris Gorelik investigates.

Mrs Emma van Heerden believes she can’t tell me much about the Cullinan Diamond, whose polished fragments are the most valuable gems of the British Crown.

Indeed, why would the lady who has spent all her life in Warmbaths, far the Tower of London where the Crown Jewels are kept, know anything interesting about the world’s most famous crystal?

Perhaps because she is the closest relative of the man who picked it up at the mine.

‘I’m the youngest of his grandchildren’, Mrs Van Heerden says. ‘I’m the only survivor.’

We sit down for a little chat.

On her mother’s side, Mrs Van Heerden is ‘heeltemaal Afrikaans’. But her father was ‘a real soutie in everything’. Her grandfather was Frederick Wells, born in Kent and raised in South Africa. ‘An old Kimberley hand’, they called him at the Premier Mine in the Transvaal.

Though not endowed with a considerable stature (he would be the only man standing in group photos), Wells had a comprehensive knowledge of diamond mining. That’s why Thomas Cullinan, the owner of the Premier, appointed him surface manager.

As a child, Mrs Van Heerden heard a story told by her father and uncles at a family reunion. They were remembering the day when the giant diamond was found.

At the end of the shift, a black miner came up to Wells and told him about an extraordinary crystal he had spotted in the side of the open pit.

‘But if you take that stone,’ the miner said, ‘you’ll be very sorry. It will bring you bad luck. Better leave it until tomorrow and let someone else find it.’

‘Don’t be silly’, answered Wells. ‘I’m not having the stone for myself. I’m going to hand it over to the general manager.’

So he went there and saw the shining half-embedded crystal, just five metres below the ground level.

Wells took out his pocketknife and tried to remove the stone from the earth. The stone refused to give in. Wells pressed harder — and the knife blade broke off near the handle.

While digging the ground around the crystal to retrieve it, he still doubted that it could be a diamond.

‘Some practical joker, thought I, has planted this huge chunk of glass here for me to find it’, Wells admitted later. ‘He thinks I will make a fool of myself by bringing it into the office in a great state of excitement, and the story will be told far and wide in South Africa.’

When the crystal was cleaned and weighed, it turned out to be over three times heavier than any diamond that had ever been known.

The unusually transparent stone weighed around 622 grams, or nearly 3,110 carats. It was the size of a man’s fist.

The mine paid Wells a £2,000 bonus for his find.

That night, according to Mrs Van Heerden, his house burnt down to the ground.

‘The fire started when the family was sleeping’, she says. ‘They managed to escape, but their belongings were gone. And all my granddad was left with was the two thousand pounds!’

Mrs Van Heerden recounts that her father, uncles and aunts had burn marks on their hands and faces from that night.

What’s also remarkable is that when Wells died, his assets amounted for a little over £2,000.

The Cullinan Diamond was shipped to London, where it remained in a bank safe for the following two years, waiting for a buyer.

Eventually, Prime Minister Louis Botha persuaded the Transvaal legislature to purchase the crystal from the state funds and present it to King Edward VII as a sign of loyalty from the new British colony.

Why would a Boer War hero initiate such move?

Maybe he was hoping that the extravagant gift would dispose the British to providing the multimillion loan the Transvaal tried to secure.

With no buyer in sight, Sir Thomas Cullinan was willing to make concessions. Botha could to pick up a bargain.

According to the official documents at the National Archives in Pretoria, the Transvaal Government purchased the Cullinan for £58,350.

This would have been an equivalent of today’s R85 million.

The prodigious stone was carved up into several gems. Two of them are the biggest white polished diamonds on the planet.

The Great Star of Africa (530 carats) is mounted into the head of the Royal Sceptre. And the Second Star of Africa (317 carats) adorns the Imperial State Crown.

‘Those are the most important diamonds in the world’, says Caroline de Guitaut, senior curator at the Royal Collection Trust. Her job is to preserve the priceless gems for the future generations. ‘They are so highly rated not only for their size but also for their purity.’

De Guitaut tells me that the rest of pieces cut from the original Cullinan form part of the Queen’s personal jewellery. They are stored at Buckingham Palace.

Outside of England, the only place in the world where you can find fragments of the Cullinan Diamond is Pretoria.

After the crystal was cut in Europe, ten carats of unpolished chips were remaining. The value of these ‘loose ends’ was purely historical. But General Botha decided to prevent them from falling into private hands. He had the Transvaal Government buy them from the cutters.

The ivory box with the chips was enclosed in a cardboard box, placed inside a tin cigarette box — and sent to South Africa by post.

In 1910, the director of the Transvaal Museum received the loose ends. In an official letter, he assured the government that they would be ‘exhibited along with the model of the original stone’.

But don’t look for them among the exhibits of the National Geoscience Museum in Pretoria. Despite their importance, the pieces of the Cullinan Diamond are not on public display.

If you want to see where Wells picked up the famous crystal, go to Cullinan. It’s a quaint village about 40 km northeast of Pretoria, with jacaranda-lined streets and views of the Magaliesberg.

Even the playground here is designed around the mining theme. Waggons, cranes and other equipment are there for kids to climb on.

Once or twice a month, a steamer brings tourists from Pretoria to the local defunct railway station. At other times, they come on their own — up to several hundreds a day in high season, from September to December.

Cullinan’s salient feature is the open pit. It’s the biggest manmade hole in Africa: 1000 m long and 400 m deep.

Right next to the pit are the buildings of the old Premier, which is now called the Cullinan Mine. It belongs to Petra Diamonds, an international diamond-mining group headquartered in the UK.

Petra bought the mine from De Beers for a billion rand in 2008. Its historic importance was of no primary concern. The carrot-shaped pipe at Cullinan is potentially the second largest diamond resource in the world.

The underground workings are 800 m deep, and there are still immense deposits of diamonds underneath. It’s estimated that the old mine would yield 200 million carats.

The process of extracting the precious crystals is extremely laborious. To recover just ten grams of diamonds, Cullinan miners process a hundred tonnes of ore.

Every fourth jumbo diamond in the world is produced at this mine. But why has none of them matched the legendary Cullinan yet?

I asked Jim Davidson, the technical director of Petra Diamonds. He’s an acknowledged authority on kimberlite geology and the optimal recovery of diamonds.

There’s no reason why the Cullinan orebody can’t produce another giant, Davidson says. ‘For instance, we have recovered the 507-carat Cullinan Heritage, one of the world’s highest quality white diamonds.’

But an enormous crystal like the Cullinan might not survive the processing. I suspect that several of them have been ruined within the last 100 years.

‘You need to configure your ore crushers to protect exceptional stones, otherwise they can be shattered’, Davidson explains. ‘Our processing plant is not yet set up to protect stones quite as large as the Cullinan diamond, which was around 10.5 cm in its longest dimension.’

For Petra, it is vital to upgrade the plant, and Davidson assures me that this will be done quite soon.

Only a few big diamonds are recovered worldwide every year. They sell in a separate market, appealing to ultra-wealthy buyers who wish to own a masterpiece of nature. ‘They’re an important subsector of their own’, adds Davidson.

In 2010, the Cullinan Heritage was sold for over R267 million — the highest price on record for a rough diamond.

Adjusted for inflation, it’s several times more than what was paid for the Cullinan Diamond. Another proof that the rich are getting richer?

Field trips

Field trips  Sponsorship & expo

Sponsorship & expo  Registration

Registration Tours

Tours  Promotion

Promotion

Conference Programme

Conference Programme  Field trips

Field trips  Sponsorship & expo

Sponsorship & expo  Volunteer

Volunteer  GeoHost

GeoHost  Registration

Registration Tours

Tours  Promotion

Promotion  Publications

Publications